Kenney Family Peru Trip

The Places

Arequipa

Arequipa sits on a desert plain at about 7,500 feet – the lowest spot on our tour and thus a good place to start. It is surrounded by three volcanoes, two active and one dormant. The volcanoes are topped with snow. The snow line this close to the equator is at 13,000 feet. Here are views in two directions from a vantage point at the edge of town.

(from Adam’s livejournal on August 26th: Arequipa):

Arequipa is known as

"The White City". The appellation has a dual etymology: now, because

a characteristic white sedimentary stone composes many of its structures. And

long ago, because the Spaniards would not allow the native peoples to dwell

there, coloring its name with their skin.

The traffic here is interesting, consisting mostly of nearly identical tiny

taxis that zip about recklessly, weaving through hairpin turns, cobblestone

streets hardly wide enough to permit them passage, and clumps of careless

pedestrians. Tour buses are also a notable presence, while personal automobiles

are hardly ever to be seen.

Dogs roam rooftops and hunker about before buildings, some accompanying owners

and others lacking them. I've seen merely one single cat, though it was quite

amicable.

A mountain near the city had its vegetation cleared in the shape of an enormous

cross, hovering above houses and shops with a ghostly, imposing presence.

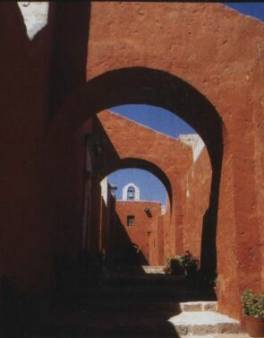

With Arequipa as our first stop – a sophisticated city of over a million people with a mainly Spanish heritage, we didn’t immediately sense how different the people of Peru are. We experienced it as an unusually clean city with dizzying traffic and many churches. Its Catholic background is far more evident than any indigenous one. The convent of Santa Catalina was particularly striking. Here, rich families would send their younger daughters (the lucky ones, perhaps; others being required to marry whatever man their parents considered a suitable financial match), along with enough money to build themselves a small house. And so the convent became a small city with its own streets and courtyards, within but entirely isolated from the surrounding city. I found the colors, the proportions of the spaces, and the peacefulness of the place stunning.

Colca Canyon

The Colca Canyon is dizzyingly beautiful. We didn’t expect this. Its terraces date back to the Inca period and before. Many of them are tiny. Forget tractors. I was struck by the integration of the manmade and the natural parts of the landscape.

(from Adam’s livejournal entries on August 26th

: Mountains and 30th: Colca Canyon):

Passing through

remote peaks towards Colca Canyon, the distant slopes rose like apparitions

from the mists to greet or warn us, before receding again into the sky. It

snowed for a time, light crystalline flakes that vanished as though imaginary.

We passed countless roadside markers - graves; sculptures; tiny house-shaped

shrines containing holy likenesses; piles of stones left by travelers for luck.

Even mid-winter, there are smatterings of green in the arid terrain, especially

in the irrigated deep valleys.

A number of active volcanoes loom here and there upon the horizon, including

"Misty Volcano", whose peak is continually shrouded in condensing

steam.

Entire mountains are roughened with tools to what seems, at distance, to be a

gruff, jagged aspect. Inexhaustible terraced slopes evaporate at their

snow-drenched peaks into the chill crisp white elevated air. There is a

continuum here between land and sky.

I was going to add to these photos of Adam’s, Margot’s, and mine a scanned postcard or two showing the canyon in its jeweled summer greens, but as I look at our austere winter photographs, I find I don’t want to. It was perfect exactly the way it was.

Here, too, we began seeing people in traditional dress – some dressed up for the tourists, to be sure, but others just wearing their normal clothes. And the people had no hesitation about bringing their animals along (and even sharing!).

Adam continues:

Though beautiful, these vistas have a drawback: I spent one morning

altitude-sick, brought low by headache and nausea, having failed to acclimatize

as gracefully as I'd hoped. Some combination of instant coffee, coca tea,

painkillers, and rubbing alcohol at the temples and below the nose fixed me up

handily, however, despite a long and bumpy bus-ride that morning.

Our tour took us up

and up winding one-lane mountain roads towards Colca Canyon, a cleft in the

landscape twice as deep as the Grand Canyon. En route, we drove through

farmland and little towns with cacti growing endlessly atop haphazard stone

walls. Upon arrival, we watched almost a dozen condors wheeling above the

emptiness on spiral currents of air. (They are considered symbolic of

Hanampacha (Heaven) by the Quechua people, and with the birds' three-meter

wingspan, it was easy to understand why.)

Then I accidentally deleted all the photos I had taken up to this point.

I (Ginger), however, who took fewer photos, did manage not to delete mine. Here are some pictures of condors soaring the air currents of the canyon. The first is mine; the second is from a postcard. Adam’s narrative continues after the pictures.

Returning, we took a detour to visit a place whose name I didn't catch, but

which I shall call the Ceiling of the World. It got colder and colder as we

ascended, until leaving the van, we stood in inch-deep snow. It was relatively

flat here, and as far as they eye could see, small stones were piled into

lopsided columns. It's a tradition for travelers to carry stones from their

origin and deposit them here, making a wish for luck, a safe journey, or

whatever else. I had brought no stones, but I made a wish regardless - it was

impossible not to be struck by the sacredness of the place.

Indeed, we were all struck by it. Adam, Margot, and I all took pictures. A few of these are below. Despite the differences in tone, these were all taken at the same time and in the same place.

Now that I think about it, this may explain why we bought alpaca blankets in Arequipa. Here is Adam wrapped in his own personal “cloud” (his description) in the airport in Arequipa, waiting for the plane to Cuzco.

Cuzco

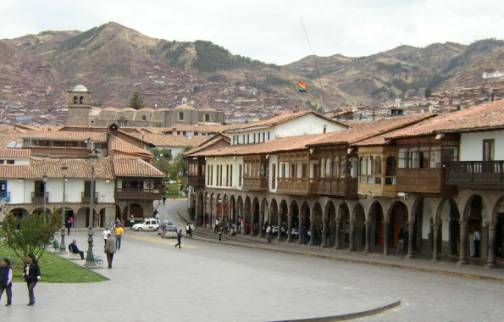

I believe that Cuzco is one of the United Nations’ World Heritage sites. Its Inca roots run deep, both in its people and in its physical manifestation. Cuzco, coming from the Quechua word meaning “navel”, was the original home of the Incas for centuries – long before they became an empire. It is the navel of the world, according to the Quechua people. Four roads lead from it to everywhere else. The four directions of the Inca cross and the circle in its center reflect Cuzco’s centrality. In the year 1438 a neighboring tribe attacked Cuzco. The Inca (meaning in this case, the head man) fled. His son and heir also fled. A younger son determined that he would defend the homeland to the death if need be, and he recruited a number of young, patriotic fellow tribesmen to remain and fight. The story is that the very stones of Cuzco rose and fought alongside its citizens, and the enemy was defeated. The old Inca and his heir were shamed and had to leave. The younger son, Pachacuti, became the Inca, the first who expanded the tribe into an empire, and who began the construction of the most well-known Inca sites – Sacsayhuaman near Cuzco, Ollantaytambo, and of course, Machu Picchu (none of which was actually completed during the hundred years’ rule of the Inca empire).

Cuzco still sits in its mountain-embraced valley at 11,500 to 12,000 feet. (Note the main central plaza in the second picture.)

The city blends the remains of the ruined Incan city with the Spanish architecture built on top of and around it. The seams are flawless. The city is beautiful.

Here is the main plaza, the Plaza des Armas.

And here are some other beautiful architectural details.

A building with a dramatic corner roofline and Spanish doorway turned out to be built atop an original Inca wall. This wall continued up the street for some distance.

Today, Cuzco is the third or fourth largest city in Peru, with a population of about 300,000. It seems that about half of these people work in craft shops, restaurants, hotels, travel agencies, and other parts of the tourist industry; and the other half are street vendors, aggressively and persistently pushing their wares to the tourists. Most of these people look decidedly indigenous. And, like their city, they are beautiful.

(from Adam’s livejournal on August 30th: Cuzco):

Cuzco, where I am

again staying, was the Quechua people's puma-shaped "navel of the

world", now a city of Moorish blue doors. Many of its Spanish-colonial

buildings rise from the original smooth obsidian foundations, which still stand

some five hundred years after their construction.

What remains of the Incan Temple of the Sun is currently entirely within a

Dominican monastery, which was built upon and around its ruins. This was not

understood until 1950, when an earthquake broke away some of the plaster that

had been applied to the original obsidian walls. (Funny anecdote: seeing a room

that had small holes built into the bottom of one wall, archaeologists assumed

that it had been used for human sacrifices, the holes providing drainage. So

they labeled it the "Chamber of Sacrifice" and dragged in an altar

stone from a different site entirely, and for many years this is the story that

tourists were told. Then, maybe three years ago, someone looked at the walls,

which were all slanting away from the interior of the "room", and

realized that the space had been on the exterior of the Temple. The holes were

for ventilation. It was outside the building. End anecdote.)

Cuzco is also home to the original Spanish cathedral in Peru, now about four hundred

years old, and a rival in size to nearly any cathedral in Europe. It contains

about four hundred and eighty paintings created by Quechua converts who were

taught the Renaissance style of painting by an Italian master sent to Peru for

this purpose. One of these paintings was long mistaken for a Van Dyke. Others

subtly incorporate pieces of the natives' original mythology. Perhaps the most

awesome is a rendition of the Last Supper featuring the local cuisine - the

centerpiece of the meal is a roasted guinea pig on a platter.

The finest hotel in Cuzco is one that we did not stay at, called the

Monasterio. It is, in fact, an antique monastery, brimming with exquisite

artworks. In the center of its flowering courtyard is the last of Cuzco's

native cedar trees, which have otherwise been chopped for wood and overrun by

the rampant imported eucalyptus. We did enjoy a very fine dinner at this place,

however, our table abutting a wall hung from end to end with perhaps a hundred

antique mirrors of all shapes and descriptions. One of the desserts included a

sorbet made from blue cheese, which tasted about like one would expect.

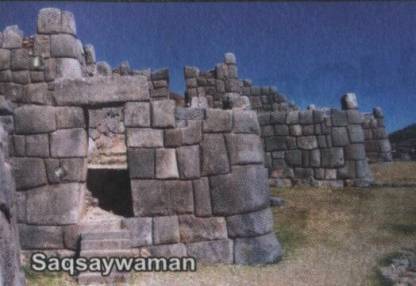

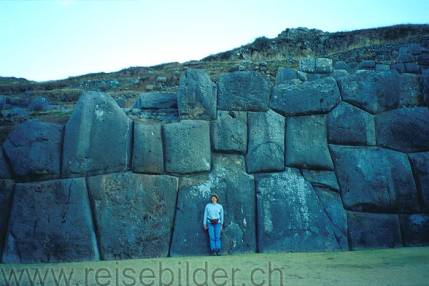

It is said (and the old Quechua street names seem to confirm) that Cuzco was originally built in the shape of the body of a puma, as seen from the air. The street called “Spine of the Puma” extends up its neighboring hill to where Pachacuti built Sacsayhuaman, perfectly placed and designed to be the head of the puma. I wish I had more pictures of Sacsayhuaman. Its stonework is astonishing. I wish I had more pictures of it, but I have had to scrounge one from the entry ticket and one from the Web.

(from Adam’s livejournal on August 30th: Saqsaywaman):

Saqsaywaman, a

fifteen-minute bus-ride from Cuzco, is the head of the puma, a monument so vast

that it dwarfs many European castles. What seems from the ground to be a jagged

wall zigzagging for thousands of feet can be seen from the perspective of Inti,

the Quechuan sun god, to be individual hairs upon the puma's head. (The puma,

symbolizing the lands below Heaven and above the Underworld, seems a fitting

design for a lasting tribute to Pachacutek's mortal might.) The stones, some as

heavy as 130 tons, were brought from a quarry several miles away and chiseled

into seamlessly interlocking shapes - no two alike, and many with dozens of

angles and curved sections as well. Commanded to tear down this monument after

the fall of the Incan empire by a Spanish bishop convinced that it could not

possibly have been built except by demons, many of the Quechua preferred

suicide to the desecration of so spectacular a devotion.

The Sacred Valley

The beautiful Sacred Valley stretches from Cuzco to Machu Picchu. We visited two noteworthy sites and an unusual hotel.

The town of Pisac hosts a large crafts market every Tuesday, Thursday, and Sunday. We hired a taxi to drive to Pisac and back on market day. On the one hand, we had already been in Peru long enough for most of the crafts to start looking endlessly similar. But a weaver and a dye-merchant caught my eye.

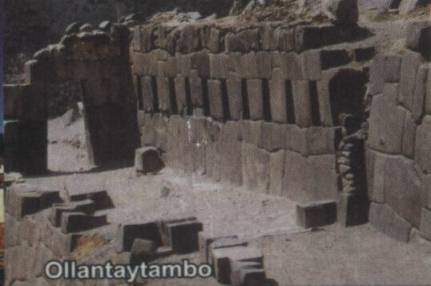

Ollantaytambo is the site of an impressive Inca fortress. That is, we call it a fortress because of its massive walls and nearly impregnable position, but like Saqsayhuaman, it was much more than that. It contained houses, terraced agricultural areas, temples, waterworks, and other functions. It may have been built as much as a work of religious art and political intimidation as for any defensive purpose. But it served the Incas well as a defense, as the site of the only actual defeat of the Spaniards. (Alas our too-few photos. The second picture is from the admission ticket.)

Ollantaytambo is also a center of local homebrewing, marked by the erection of colored plastic bags on poles to indicate the type of homebrew currently available.

(from Adam’s livejournal on August 30th: Vistadome):

We rode from

Urubamba to Machu Picchu, and then from Machu Picchu back to Cuzco, on a

"vistadome" train, its windows extending into the ceiling for a

better view of the towering mountains. The most annoying feature of this trip

was the piping music that they ceaselessly blasted into the cabins, which I had

already been growing tired of some days before, since every restaurant here has

its own ethnic band. The one-hour trip to Machu Picchu was bearable, but the

four-hour ride to Cuzco was positively sanity-sapping. It was rendered even

more surreal by an on-board alpaca fashion show and a ceremonial dance

performed in the aisles by a fellow dressed from head to toe in absurdly

varicolored wool. He kept romping to the front of the train car and back,

shaking peoples' hands and waving his rectangular hat in the air.

I will never forget him.

Adam neglected to mention that the gentleman in question also wore what appeared to be a white ski mask. We could hardly believe that the train would provide us the live entertainment of this exotically dressed person dancing up and down the aisles to the cheers of our fellow travelers.

Besides for the features that Adam has described, the main noteworthy feature of the ride down from Cuzco (11,500 feet) to Machu Picchu (8,500 feet) was the magnificent scenery.

To complete the climb back up to Cuzco, however, the train had to perform four switchbacks, three of them inside of Cuzco itself, zigzagging back and forth on its rails and actually traveling backward some percentage of the trip.

Machu Picchu

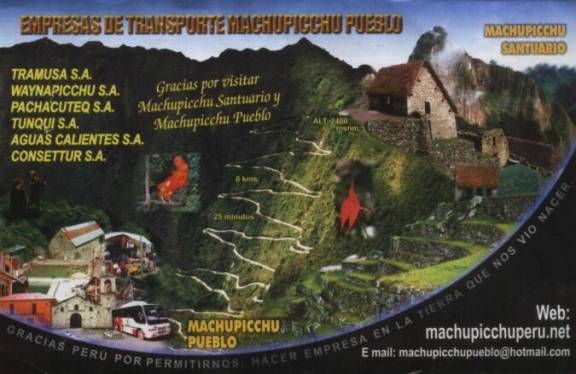

There are only two ways to get to Machu Picchu, and they both require taking the train. Some people take the train only to kilometer 82, where they meet guides for a three-day hike over the Inca Trail to descend into the city through the Sun Gate as the Incas themselves used to do. Others, among whom we number ourselves, continue on the train to Aguas Calientes (part of Machu Picchu Pueblo) and then board a switchback bus up to the historic site. The bus ticket has a graphic representation of the route:

(from Adam’s

livejournal on August 30th: Machu Picchu):

The first thing I

noticed as I stepped off the bus after a harrowing half-hour ride up one-lane

switchbacks carved out of the mountainside rainforest was the smell. It's

jungle air, rich and humid, alive with living life-ness. It smelled, in brief,

like orgones. The view was also astonishing, encompassing overlapping

jungle-shrouded peaks, near and distant, as far as the eye could see, as well

as a churning river deep below. The area is moist, with blurry clouds

perpetually clinging to the very tops of many of the surrounding mountains. It

rained for an hour the first afternoon, and afterwards a vast cloud of steam

rose from the valley into the sky; even my breath came out as steam in the

65-degree-Fahrenheit weather.

Our tour of the

ruins was draining, as I was tired for some reason and had become somewhat sick

of guided tours. It was much more enjoyable, if less edifying, to roam the

place by ourselves later on, poking our heads into three-walled houses and down

into steep dark stairwells, and watching the sunset from a high ridge next to

the Three-Window House. I won't go into the Litany of Facts here, since you can

learn as much as you want about the place online, but it's interesting stuff.

The main thing to remember is that nearly the only thing we know for sure about

the Incan Empire is that it was a terribly advanced civilization.

The hotel we stayed at, the Santuario, was effectively on-site (my parents' big

splurge for this trip). We had a fantastic view of the mountains from the

terrace-doors of our rooms. An exceptional dinner was included, featuring such

Peruvian flairs as marinated tree-tomatoes (sour, tangy, and fruity) and a

mousse made from pisco (a grape-derived local liqueur that is very popular

here).

The view from the room:

Shadows lengthening over Machu Picchu as the sun sets:

(Adam continues:)

We took advantage of our location the next day, getting up before dawn to hike a half-hour up to the Sun Gate, where we watched the sun rise on the ruined city.

After returning to the hotel and breakfasting, we

sallied forth again on a more adventurous excursion to the Temple of the Sun,

perched perilously atop a slender peak. The climb was difficult in the extreme

- think of a narrow 70-degree-angle stairway, worn smooth by years of use, cut

into the raw stone of a vertiginous mountain. But the view from the top,

dizzying though it was, was well worthwhile. I alone continued up into the

Temple's recesses, crawling through a cavelike passage onto sun-drenched shelves

of granite. I sat with my eyes closed for a little while, smiling and feeling

the world revolving below and around and through me.

The descent was much easier: I flew, it seemed, on condors' wings.

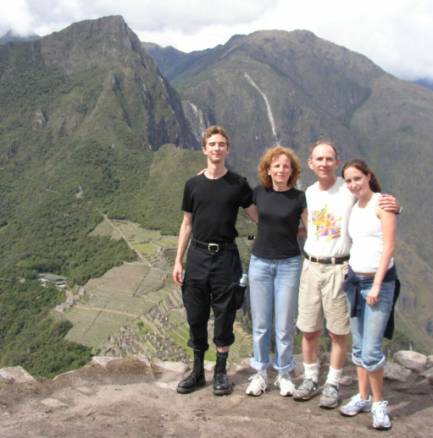

Huayna Picchu is the mountain you see in the background of all the photos of Machu Picchu. If you were going to describe it in just one word, a likely choice would be “steep”. Without Dan’s encouragement and support, not only would I not have made it; I would not have been bold enough to try. But we all did make it, and in many ways, the accomplishment was the highlight of the trip.

At the top of Huayna Picchu, with the ruins of Machu Picchu spread out below